- Fargo Season 1

- Fargo Season 2

- Fargo Season 3

- Fargo Season 4

- Fargo Season 5

When FX released the television series Fargo, I didn’t even consider giving it a chance. The entire premise seemed to be a real-life Hamlet 2, a tragic joke.

Recently, a person I respect recommended Fargo so I felt compelled to give it a shot. The first season realized some of my greatest fears, but the quality acting and cinematography make it an enjoyable show overall. Fargo, the series, most suffers from inevitable comparisons to Fargo, the movie. As a continuation of the film in the Fargo universe, the series copies the most superficial aspects of the movie while failing to adopt the most important components that made it so compelling. The showrunners would have had a much better show had they done something similar without the albatross of Fargo hanging around its neck.

What’s Good about Fargo?

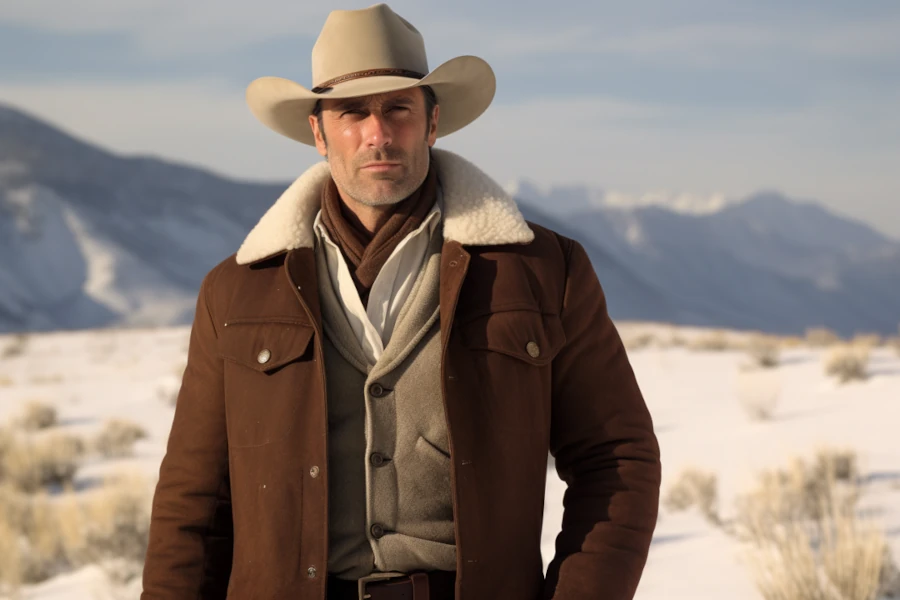

I should mention that, despite the merciless criticism that follows, Fargo does certain things extremely well. The cast and their performances present the appearance of a cinematic triumph. Billy Bob Thornton, in particular, makes the most of his character. The actors elevate the material with performances that cover up the deficiencies in the writer’s room.

Likewise, the excellent cinematography works to veil the absurdities it depicts, visually preoccupying the audience to distract attention away from the doofus behind the curtain. If you were to just watch the show on mute you would assume it’s a top-tier production. Scenes are well set up and the pacing between them could not be better. Visually, it’s clear that these filmmakers closely studied and copied the Coen brothers. That’s a good thing.

The score really ties things together. It does steal from the film, but even when it doesn’t the score perfectly punctuates every scene. Loud percussive moments when bad guys walk toward impending destruction blend together an irresistible visual-sonic cocktail. The pairing of music and visuals make Fargo a top notch production. All of this results in a show that is more Quentin Tarantino than Coen brothers. Basically, it presents the highest level of filmmaking in every category except the writing. As with Tarantino, it appears to be high art to the unsophisticated, while bittersweet to those who prioritize storytelling.

Same name, different universe

The Fargo series resides in a different universe than the movie, and as penance it provides the same setting and a cameo from a certain object from its namesake. The showrunners try to convince the viewers that continuity exists between these universes by employing these tie-ins, but they only exasperate the problem by forcing more unfavorable comparisons between the two.

Fargo follows an ensemble cast tied together by crime. An assassin, Lorne Malvo (Billy Bob Thornton), hits a deer while driving on a country road. This allows his victim to escape the confines of his trunk to run off into the woods where he freezes to death in the Minnesota snow. Somehow the assassin makes it to the hospital to receive treatment for his head injury. Here’s the first major plothole. Malvo doesn’t appear to have an injury serious enough to warrant a hospital visit and it doesn’t fit his character. At the hospital he meets Lester Nygaard (Martin Freeman), a slight, cowardly man who broke his nose in an embarrassing incident with a bully. The bully scene will make you wonder if you accidentally clicked over to a hokey 1980s film.

The chance meeting between Lorne and Lester prompts Lorne to seek revenge on behalf of Lester and inspires Lester to become dangerously (criminally) bold. Think of it as a meet-cute for criminals. Throughout the season Lorne commits more and more brazen crimes while Lester struggles to cover up his single crime. Meanwhile, police officers Molly Solverson (Allison Tolman) and Gus Grimly (Colin Hanks) attempt to solve the crimes despite impediments from their incompetent bosses.

Plot holes, the unbelievable, and serendipity abound. It’s like the showrunners decided to merge the style and tone of Fargo with the realism of The Hudsucker Proxy.

Different rules

Every piece of fiction establishes rules that must be followed to maintain the suspension of disbelief. The rules in the Fargo series, as incredulous as they are, would actually hold up if not for their incongruity with the source material. It’s almost as if the show was made for people who have not seen the movie.

The holdover material especially clashes. Each episode begins with the infamous disclaimer from the movie proclaiming the story to be true with only the names changed. The authenticity of the film made this work. The rules in the movie are the rules of real life. The Coens seek to convince the audience that the opening disclaimer is true, and this realism raises the stakes and the tension.

For the television series, the beginning disclaimer appears to be nothing more than a joke. It’s just there to remind you of the movie. Reality has no bearing in this world, especially regarding the criminals. They brazenly commit crimes in broad daylight with no repercussions. They have impeccable timing. They’re maestros of combat. One walks away from getting caught in a bear trap as if he sprained his ankle. These are the rules of pulp.

Pulp fiction rules do not invalidate a story or make it bad, but they are incompatible with Fargo, the movie.

Caricatures replace characters

Characters made Fargo (the movie) believable. The series provides caricatures that are often poor replicas of the movie. Two mob enforcers, Mr. Wrench and Mr. Numbers, take the bad guy dynamic from the film to its most extreme. In the film, the criminal duo consists of a jabbermouth and a stoic. Here, they go all out and make one of them deaf.

Most of the major movie characters have a comparatively bland series analog. The Minnesota nice female cop who attacks each scene with optimism. The down-on-his-luck weakling who instigates a series of crimes in a moment of desperation. While an entire television season should provide time to flesh out these characters in ways not possible in a single movie, the series somehow fails to even make these characters commensurate with their inspirations.

The characters who should have arcs do not. Molly Solverson doesn’t have to grasp with the reality that life is more vicious than she imagines. Her unflappable optimism and sunny disposition do not stem from ignorance and environment, but appear to be innate. Her counterpart, Gus Grimley, grapples with this conflict from the moment his we meet him. His existential struggles may be the only interesting character development, but his “arc” is merely the classic nerd who stands up to a bully.

There are several other caricatures, two of which really drag the show down. Making things worse, these two characters are played by the best actors in the show. First, there’s Lorne Malvo. Thornton gives this character his all and does an excellent job, but the character just doesn’t make sense in the Fargo universe. He’s Anton Chigurh (No Country for Old Men) with southern charm.

Chigurh works in No Country because he has a supernatural quality about him. Functionally, Chigurh is a horror movie monster. It would be inappropriate to view Chigurh as a caricature because he is so abnormal. Chigurh is a symbol. A personification of evil. Malvo has the same invulnerability and penchant for evil, but he’s not in a horror movie. Worse yet, his pontificating makes him a typical villain. Wearing plot armor with a single chink—the season finale—Malvo also has a predictability that dulls his effect.

Bob Odenkirk plays another egregiously bad character, Chief Bill Oswalt. His entire personality has been molded by his function as a plot obstacle for Molly. Every line, every action, is an illogical impediment to Molly completing her job. To say this character feels fake is an understatement. In season 3 they reprise this same plot device and just change his personality.

The caricature problem extends to pretty much everyone in the Fargo universe. How the writers found this acceptable when basing their show off such a character-rich movie just doesn’t make sense.

A conflict of meaning

Art has purpose. Ultimately, we can distinguish art from a doodle because art is rhetorical. It communicates. It doesn’t have to communicate the meaning of life or provide profound morals, but art tells us something.

Fargo, the movie, tells us about people who do bad things. The darkest aspects of humanity are present even among our most polite and seemingly docile communities. Given the right circumstances, anyone may be susceptible to committing horrific acts. People do not commit criminal acts because they’re evil, but because they arrive in a circumstance where they believe the reward outweighs the risk. Criminals are dumb or desperate. They may also be immoral, but even the immoral recognize that risk accompanies crime.

In Fargo, the series, we are given the same setup of a normally law-abiding citizen pressured by circumstance into criminality. But there are two main differences: 1) The criminals Lester Nygaard associate with are just criminal by nature and casually commit crimes wherever they go 2) Crime transforms Lester Nygaard into a deviant but Jerry Lundengaard (William H. Macy) has no such arc.

We do not receive any backstory for the Fargo crime syndicate or the weird international society of assassins Lorne Malvo works for. Some of this comes in later seasons, but it’s so full of plot holes it just makes things worse. Instead of some plausible explanation for these things, the show wants us to believe that there are sprawling criminal organizations that nonchalantly break the law and do not worry about legal repercussions. That they don’t have to worry about repercussions because local law enforcement is willfully ignorant to criminal activity and the FBI has an incompetent Key & Peele on the case.

In this way the main criminal characters—Lester Malvo, Mr. Wrench, and Mr. Numbers—all just exist as if they came out of the womb super-criminals. They are like super villains from terrible comic books. It doesn’t make sense why they are so proficient while engaging in criminal activity that only a moron would partake in. These types of people don’t exist in the real world.

Carl (Steve Buscemi) and Gaear (Peter Stormare) from the Fargo movie, however, make complete sense as the types of guys who would kidnap a woman for tens of thousands of dollars. They’re losers. Like most criminals, they’re incompetent and this swiftly leads to their demise. In this regard, Lundengaard has more in common with his conspirators than he would ever admit. Fargo, the movie, tells the audience something about the nature of crime, whereas Fargo, the series, recycles TV tropes about crime.

Comparing Jerry Lundengaard to Lester Nygaard also demonstrates the nuance being stripped from Fargo. The lack of an arc allows Jerry Lundengaard to function as a classic tragic hero—his flaws make him incompatible with the world and cause his demise. Lester’s backstory mirrors the villain backstories from comics: an incident transforms him from an innocent, law abiding citizen to a relentless, remorseless villain. It’s like villainy is a disease that one catches.

Fargo, the series, tells of a binary world. Characters are divided into good or evil. Competent in all things or incompetent in all things. Fargo, the move, reflects the multiplicity of reality.

The only time the series has the courage to approach reality is in the dialogue of Lorne Malvo. He views human interactions as predatory. Malvo thinks of himself as a wolf and this comparison is made several times. If only the showrunners had the courage, Malvo could have been made more realistic and functioned as the real tragic hero. But they cut him short of real insight. At one point, Molly’s father presents a factually incorrect retort to Malvo’s worldview: “Animals only kill for food.” This line encapsulated the whole show for me. The writers thought they had something slick but couldn’t be bothered with the necessary research.

Fargo was created at a time when amazing television shows were overtaking feature length movies as the most compelling way to tell a story on film. Starting with The Sopranos, networks brought more and more movie elements into television: big budgets, A-list actors, and top-notch writing. Fargo adopted these first two elements but clearly relied on traditional TV writers. This results in a bunch of cliches and tropes performed excellently, wrapped in excellent cinematography and music.